How the Five Pillars of Islam Shape Faith and Community Life

This work has been verified by our teacher: 16.01.2026 at 19:10

Homework type: Essay

Added: 16.01.2026 at 18:21

Summary:

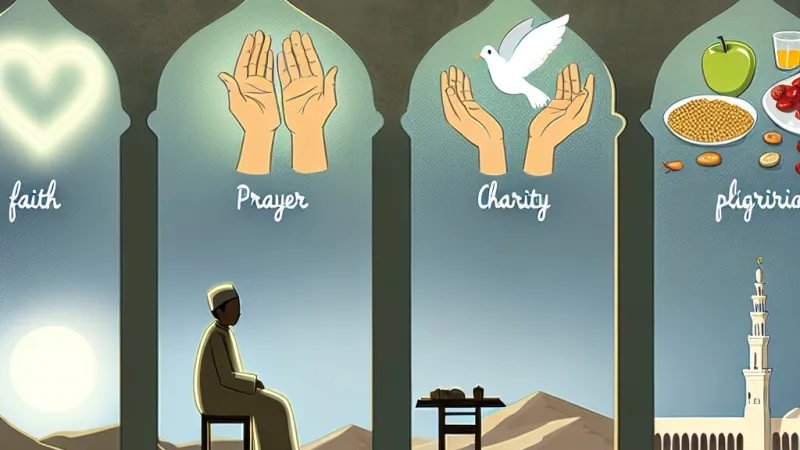

Shows how Islam’s Five Pillars—faith, prayer, charity, fasting, pilgrimage—anchor belief, ethics and community amid historical and modern diversity.

How the Five Pillars Shape Muslim Belief, Practice and Community Life

Throughout history, religions have maintained their coherence, not only through shared beliefs but through structured practices that bind their adherents into communities. In Islam, this rigour is exemplified by the Five Pillars, foundational duties which guide individual conscience, communal life, and the broader Islamic sense of morality. The Five Pillars—Shahadah (faith), Salah (prayer), Zakat (charity), Sawm (fasting) and Hajj (pilgrimage)—do not merely represent ritual acts; rather, they weave together the spiritual, ethical and communal fabric of Muslim existence. This essay will consider their theological roots, practical details, lived expression, and social significance—while also reflecting critically on how the pillars continue to shape, and sometimes challenge, Muslim life today.Historical and Theological Foundations of the Five Pillars

The Five Pillars emerged from the formative period of Islam in seventh-century Arabia, with the Prophet Muhammad both articulating and exemplifying them as binding duties for the growing Muslim community. Drawn from Qur’anic precepts and elaborated through Prophetic traditions (hadith), these acts are understood not as arbitrary regulations but as expressions of key Islamic values—tawhid, the absolute oneness of God, and Islam itself, meaning submission to God’s will. The Qur’an repeatedly links righteous action with faith (“Establish prayer and give zakah…” Qur’an 2:43), while hadith such as that famously narrated by al-Bukhari and Muslim declare, “Islam is built upon five…” Thus, the pillars rest on a strong foundation of scriptural and prophetic authority, codified by later scholars and jurists to ensure consistency of practice.An Overview: Functions and Categories of the Pillars

In considering the Five Pillars collectively, it becomes apparent that they address multiple dimensions of religious life. The first pillar, Shahadah, sets out the creed; Salah regulates worship at regular intervals; Zakat connects belief to social ethics; Sawm introduces seasonal, communal abstention; and Hajj stands as a crowning journey within a believer’s life. Together, these acts link internal conviction to outward action, shaping faithful Muslims physically, spiritually and communally. For instance, the internal affirmation of God’s unity in Shahadah is continually reinforced through the bodily discipline of Salah and the ethical obligations of Zakat. In this sense, rather than existing in isolation, each pillar contributes to a seamless web of belief and practice.The Shahadah: Professions of Faith and Identity

The Shahadah, or profession of faith, forms the essential threshold of Islam: “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the Messenger of God.” This declaration, brief but profound, asserts monotheism and acknowledges Muhammad’s unique role as the last prophet. Its importance in Islam cannot be overstated, serving both as the entry point for converts and the ultimate affirmation for lifelong adherents. In practical terms, the Shahadah features in daily prayer, is whispered into the ear of a newborn, and forms part of the final rites at death. Theologically, it underpins all other acts—if faith is lacking, ritual acts lose their spiritual value. Yet, the sincerity (niyyah, or intention) behind pronouncing the Shahadah is crucial; as Islamic scholars frequently note, mere verbal utterance, without conviction, does not constitute true faith. In the UK, one might observe a conversion ceremony in an Islamic centre, where the recitation of the Shahadah marks both a personal milestone and a public welcome into the community.Salah: Ritual Prayer and Spiritual Discipline

Second among the pillars is Salah, the structured obligation of performing ritual prayer five times each day. These prayers punctuate the day: before sunrise, midday, afternoon, sunset, and night—each marked by physical movements (standing, bowing, prostration) that embody submission and humility before God. Salah requires ritual purification (wudu), underlining the importance of spiritual and physical cleanliness, and is ideally performed facing Mecca, the symbolic heart of Islam. While private prayer is permitted, congregational prayer—especially the Friday Jumu’ah—is considered more meritorious and strengthens the bonds within the community.In British towns and cities, mosques act not only as places of worship but as hubs of social and educational activity, with prayers structuring daily life for many Muslims. The variety within Salah—distinctions between obligatory (fard), recommended (sunnah), and additional (nafl) prayers—allows flexibility and depth. However, modern life brings challenges: work schedules, school timetables, and commuting can make consistent attendance or performance difficult. Scholars in the UK have discussed such obstacles, sometimes issuing rulings (fatwas) that permit combining prayers in cases of hardship. Although women are not obliged to attend the mosque for group prayer, many do, and in numerous communities, separate prayer spaces and timings exist to facilitate access. This diversity highlights both the rigour and the adaptability of Salah in contemporary life.

Zakat: Obligatory Charity and Social Justice

Zakat, the third pillar, institutionalises charity as a religious duty—a way of redistributing wealth to create a more just society. Each eligible Muslim is expected to contribute a portion (commonly 2.5%) of their accumulated wealth above a certain threshold (nisab) each year to assist those in need. The Qur’an (9:60) details potential recipients: the poor, the needy, those working to collect zakat, debtors, travellers, among others. Contrary to voluntary charity (sadaqah), zakat is seen as an obligation, and the word itself means both “purification” and “growth”—indicating that through giving, wealth is spiritually cleansed, and society flourishes.In practice, British Muslims today fulfil zakat through local mosques, national charities such as Islamic Relief, and increasingly via online donation platforms. For example, one might calculate: a person with savings of £1,200 above their personal expenses for an entire year pays £30 in zakat. This structured giving supports food banks, education initiatives, and refugee work both in the UK and abroad. Nevertheless, differences exist in calculating assets, and modern complexities such as pensions and digital currency prompt ongoing debate. While the ideal is to lessen inequality, some critics question the effectiveness of enforcement and the true scope of its social impact today.

Sawm: Ramadan Fasting and Spiritual Renewal

The fourth pillar, Sawm, refers specifically to fasting during the lunar month of Ramadan. During these thirty days, practicing Muslims abstain from food, drink, and other physical needs from dawn until sunset. More than a test of physical endurance, Sawm is designed to cultivate self-discipline, empathy for the hungry, and heightened spirituality. The month is marked by increased worship, with special nightly prayers (taraweeh) held in mosques, and personal acts of reflection and charity.Observing Ramadan in Britain brings a unique cultural twist. Often, families rise early to eat suhoor and break fast together at iftar, with mosques organising community meals. Schoolchildren and workers may face challenges in maintaining energy or navigating non-Muslim environments, though many schools and employers are increasingly sensitive to the needs of Muslim students and staff. Exemptions exist for the sick, elderly, pregnant women, and travellers, reflecting Islam’s accommodation of vulnerability. Missed fasts are made up or, in some cases, compensated by feeding the poor (fidya). Stories abound of neighbours exchanging food and sharing in celebration, showing that Ramadan, far from being a purely private exercise, infuses local communities with new rhythms and shared experiences.

Hajj: Pilgrimage as a Culminating Act

Finally, Hajj represents the pinnacle of Muslim life, a once-in-a-lifetime obligation for those physically and financially able to undertake the journey to Mecca. Pilgrims enter a state of spiritual purity (ihram), donning simple white garments to symbolise equality, and perform a sequence of rituals: circumambulation (tawaf) around the Kaaba, walking (sa’i) between the hills of Safa and Marwa, standing in prayer at Arafat, and the symbolic stoning of pillars at Mina. Taking place during the twelfth lunar month, Hajj attracts millions and creates a palpable sense of global unity that transcends race, nationality, and social class.For British Muslims, the journey to Hajj is a profound experience, often preceded by months or years of saving and preparation. Muslim travel agencies in Manchester, London, or Birmingham help with visas, flights and guidance, while the British Council of Hajjis provides information and health advice. However, practical barriers persist: strict quotas, cost, and logistical challenges can restrict access, and recent debates have addressed the environmental impact of mass travel and ethical questions surrounding commercialisation. Umrah, the “lesser pilgrimage,” is not obligatory but often sought as a spiritual complement, further illustrating the diversity of pious aspiration within the tradition.

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in