Cell Structure: How Form Supports Function in Plant and Animal Cells

This work has been verified by our teacher: 16.01.2026 at 21:15

Homework type: Essay

Added: 16.01.2026 at 20:56

Summary:

Explore Cell Structure and how form supports function in plant and animal cells; learn key organelles, comparisons and exam-ready notes for secondary students.

Cell Structure: Connecting Architecture to Function in Biology

A cell, often described as the basic unit of life, is the smallest entity capable of independent existence and of performing essential biological functions. This simple statement underpins a complex and marvelously organised world that has captivated generations of British scientists from Robert Hooke—whose sketches of cork cells first introduced the concept in the 17th century—to present-day researchers in molecular biology. The central aim of this essay is to unravel the major structural components of cells, illustrating how each element’s design reflects its vital role in cellular physiology. Furthermore, the essay will contrast the main types of cell organisation, introduce the leading methods for studying cellular structures, and highlight their physiological and medical significance. In exploring animal and plant cells (with nods to the simpler prokaryotes), I will demonstrate that structural specialisation is the foundation upon which cellular function is built.

---

The Cell as the Fundamental Unit: An Overview

All living organisms—be they a blade of grass in a Dorset meadow or the liver in a human body—are composed of cells. There are two universal categories of cells: prokaryotic cells, typified by bacteria, and eukaryotic cells, which make up fungi, plants, animals, and protists. Eukaryotic cells are distinguished above all by their compartmentalisation: their internal membranes create separate, bespoke environments for the diverse chemical reactions needed to sustain life. This functional zoning allows for far greater control and efficiency, a key advantage that underpins multicellularity and the diversity of higher life forms. Central to all cells, however, is the cytoplasm—an aqueous soup charged with dissolved ions, small molecules, enzymes and, in eukaryotes, a multitude of organelles. Within this cytoplasmic context, steep gradients of pH, ion concentrations and metabolites can be established, enabling intricately regulated processes.---

The Plasma Membrane: Gateway and Guardian

Composition and Organisation

The first boundary of every cell is the plasma membrane. Composed primarily of a phospholipid bilayer, its amphipathic molecules (with water-loving heads and water-repellent tails) arrange themselves to form a flexible, semi-permeable barrier. Embedded within this sandwich of lipids are proteins—some burrowed all the way through (integral), others attached peripherally. In animal cells, cholesterol molecules are interspersed, acting as a fluidity buffer, particularly vital in the fluctuating British climate as temperatures fall and rise.Carbohydrates protrude from the membrane in the form of glycoproteins and glycolipids, forming a cellular ‘signature’ crucial for tissue formation—a phenomenon observed in classic experiments by British developmental biologists investigating amphibian embryos. This recognition system also underpins immune surveillance and infection responses.

Functional Mechanisms

The membrane is not merely a static barrier but a dynamic interface. Passive transport—including diffusion and osmosis—permits the movement of small molecules along their concentration gradients, a process essential in, for instance, oxygen transfer in red blood cells. Facilitated diffusion via protein channels speeds up movement for specific substances, like glucose via GLUT transporters. Active transport mechanisms, reliant on ATP, enable the cell to maintain ionic asymmetry; the classic example is the Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase pump, described extensively in physiological literature in the UK. Bulk movements of material occur via endocytosis (taking in) and exocytosis (export), coordinated through vesicle budding and fusion.Specialised Surface Structures

Some cells sport microvilli—finger-like projections best known from the epithelial cells lining the human small intestine, enabling increased absorptive surface. Others, like the ciliated tracheal cells in the lungs, possess beating cilia composed of microtubules whose coordinated action helps clear particulate matter, as seen in smokers who lose this function. Spermatozoa, the only human cells with a true flagellum, testify to structural specialisation underpinning movement and function.---

Cytoplasm and the Cytoskeleton: Cellular Architecture in Action

The cytoplasm acts as both the site and solvent for most enzymatic reactions and metabolic pathways. However, it is the cytoskeleton—a dynamic network of protein filaments—that brings organisation, strength, and movement to the apparent chaos.- Microfilaments, composed mainly of actin, support the cellular cortex, drive amoeboid movement, and—most vitally in humans—enable muscle contraction. - Intermediate filaments such as keratins reinforce mechanical stability in epithelial cells, preventing rupture under stress. - Microtubules, made from tubulin, chart intracellular highways for the transport of vesicles and position chromosomes during mitosis; their discovery in dividing onion root tips is a staple of British school microscopy lessons.

At the heart of the microtubule network often lies the centrosome, organising the mitotic spindle and, in animal cells, housing centrioles. Plant cells typically lack centrioles, an important distinction in cellular biology practicals in the UK curriculum.

---

Membrane-Bound Organelles: Compartmental Powers

The Nucleus and Nucleolus

The nucleus is cell headquarters: its double-membrane envelope, studded with nuclear pores, isolates the genetic material—DNA—while still permitting regulated exchange. DNA’s association with histones forms chromatin, oscillating between the loosely packed euchromatin (active) and dense heterochromatin (silent). Within the nucleus, the nucleolus emerges as a centre of ribosome assembly, vital for protein production. The strict partitioning between the genetic ‘library’ and cytoplasmic ‘factory floor’ is essential; faulty nuclear transport leads to diseases exemplified by muscular dystrophies or certain cancers.Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)

Rough ER appears studded with ribosomes, sites of protein synthesis for secreted or membrane-bound proteins (such as insulin in pancreatic β-cells). Proteins here are folded, sometimes glycosylated, and checked for quality—a system that, when it fails, contributes to conditions like cystic fibrosis, a topic well-covered in British GCSE and A-level biology. The smooth ER is crucial in lipid synthesis, detoxification (notably in liver hepatocytes after heavy drinking or drug use), and, in muscle, calcium storage (the sarcoplasmic reticulum).Golgi Apparatus

Moving onward, the Golgi apparatus is a stack of flattened sacs (‘cisternae’) where proteins and lipids receive final modifications and are sorted to their correct destinations. Some are packaged into lysosomes, others dispatched to the cell surface or secreted. In glandular tissues, such as the salivary glands famously studied in histology practicals in the UK, the prominence of the Golgi reflects its secretory workload.Mitochondria

Mitochondria are familiar as the ‘powerhouses’ of the cell. Their double membrane encloses a matrix where the tricarboxylic acid (Krebs) cycle occurs, and the inner membrane’s extensive cristae house proteins of the electron transport chain, responsible for synthesising ATP—the energy currency of the cell. Mitochondria contain their own DNA, genetic evidence for an evolutionary origin as symbiotic bacteria. Mitochondrial inheritance and diseases (such as Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy) are classic topics in British university genetics courses.Lysosomes and Autophagy

Lysosomes—acidic vesicles packed with hydrolytic enzymes—function as the cell’s refuse collection and recycling service, degrading defective organelles and macromolecules. Through autophagy, cells cope with starvation or stress by digesting parts of themselves—a process brought to public attention in recent years through Nobel Prize-winning research.Peroxisomes

Similar in outline but distinct in function, peroxisomes are the site for breakdown of very-long-chain fatty acids and detoxification reactions. The presence of catalase allows rapid decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, a toxic byproduct of metabolism, and defects in these organelles underpin rare but severe metabolic conditions.---

Non-Membrane Structures: Ribosomes, Centrioles and More

Ribosomes are molecular machines composed of ribosomal RNA and proteins. Eukaryotic ribosomes (80S) are larger than their prokaryotic counterparts (70S), a distinction exploited in designing antibiotics that target bacterial but not human cells. Whether free in the cytosol (making proteins for internal use) or attached to the rough ER (for secretion), ribosomes exemplify how structure determines cellular logistics.Centrioles, present in animal cells, organise microtubules for cell division. Their absence in most plant cells (notable exceptions exist, but limited in flowering plants) is frequently discussed in A-level practicals and diagrams.

---

Plant Cell Specialisations: Building Beyond the Basic Blueprint

Unlike animal cells, plant cells possess a rigid cell wall constructed from cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, conferring both strength (permitting turgor) and protection. The presence of plasmodesmata—fine cytoplasmic channels—enables communication and nutrient flow between cells, a feature critical to cohesive plant tissue function.Chloroplasts stand out as sites of photosynthesis, with a double-membrane envelope and internal stacks of thylakoid membranes (grana). The stroma hosts enzymes for the Calvin cycle, while the whole organelle contains its own DNA—a reflection of its endosymbiotic origin. The presence of chloroplasts, as well as the single large central vacuole (maintaining turgor and storing waste/pigments), highlights key evolutionary adaptations. The lack of centrioles and lysosomes further sets plant cells apart in comparative diagrams.

---

Comparing Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Cells

Prokaryotic cells, such as bacteria, lack membrane-bound organelles. Their DNA forms a nucleoid region, and metabolic reactions occur on or near the cell membrane. The possession of a tough cell wall made of peptidoglycan (for most bacteria), 70S ribosomes, and—in some species—motile structures like flagella, enable these simple forms to exploit diverse ecological niches. Archaeal cells, a distinct prokaryotic lineage, have unique membrane lipids and wall chemistries, insights gained from extremophiles living in hot British springs and high-salt environments.Size limits and lack of compartmentalisation make prokaryotes quick to reproduce and adept at gene transfer (horizontal gene transfer), providing a rapid evolutionary response to changing environments—a fact underscored by the recent proliferation of antibiotic resistance.

---

The Impact of Size: The Surface Area to Volume Dilemma

Cell size is constrained by surface area to volume (SA:V) ratio. As cells grow, their volume increases more sharply than surface area, limiting nutrient uptake and metabolic efficiency. Solutions include minimising cell size, developing infoldings such as microvilli (as in small intestine cells), or (in some cases) incorporating multiple nuclei. Red blood cells, for example, lacking nuclei, optimise packing for maximal haemoglobin content—a quintessential adaptation highlighted in British school textbooks.---

Peering Inside: Methods of Cell Study

Our knowledge of cell structure has grown thanks to advancing technologies:- Light microscopy, the domain of classic practical biology lessons in British schools, reveals overall cell shape and allows visualisation of basic structures after staining. - Electron microscopy (TEM and SEM), developed in post-war London and elsewhere, has revealed the fine details of organelles: the cristae of mitochondria or the trilaminar appearance of the plasma membrane. - Fluorescence microscopy and genetically encoded tags (such as GFP) make it possible to follow the real-time movement of proteins and vesicles in live cells. - Cell fractionation and biochemical assays allow researchers to separate and study organelles in isolation, attributing specific functions to each.

These techniques, arising from a tradition of British innovation and attention to empirical detail, demonstrate that what cannot be seen cannot be understood.

---

Structure and Function: Clinical and Agricultural Impact

Faults in cell structure underpin many diseases. Mitochondrial diseases disrupt energy metabolism, while lysosomal storage disorders lead to the accumulation of undigested macromolecules. Cystic fibrosis, widely discussed in British science courses, arises from defective membrane protein trafficking, leading to thick mucus and vulnerability to infection.Misregulation of cytoskeletal or nuclear architecture is also central to cancer progression and metastasis. In the plant world, disruptions to the cell wall affect crop yield and resistance to pathogens—a concern for agriculture and global food security.

---

Evolutionary Perspectives and Synthesis

The principle that form enables function is nowhere more apparent than in the cell. Compartmentalisation, seen in eukaryotic cells, likely emerged as a response to increasing biochemical complexity. The endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria and chloroplasts reveals evolution’s penchant for recycling and adapting solutions—a perspective that continues to frame scientific investigations, including the study of symbiotic microbes resident in the British human gut.---

Conclusion

In summary, the study of cell structure is indeed the study of life’s fundamental architecture. From the flexible containment of the plasma membrane to the sophisticated choreography of organelles orchestrating energy production, information storage, and synthesis, each component is tailored to its role. These intricacies underpin not only physiology and development, but also explain many diseases. Understanding cell structure, using tools developed and refined in the UK, opens windows not just onto molecular processes but onto evolution and the full sweep of living diversity. As research presses on, revealing ever finer details—such as membrane nanodomains and organelle cross-talk—the foundational relationship between structure and function remains central. Future challenges include untangling how cells assemble and maintain their organelles, and how subtle defects tip the balance from health to disease.---

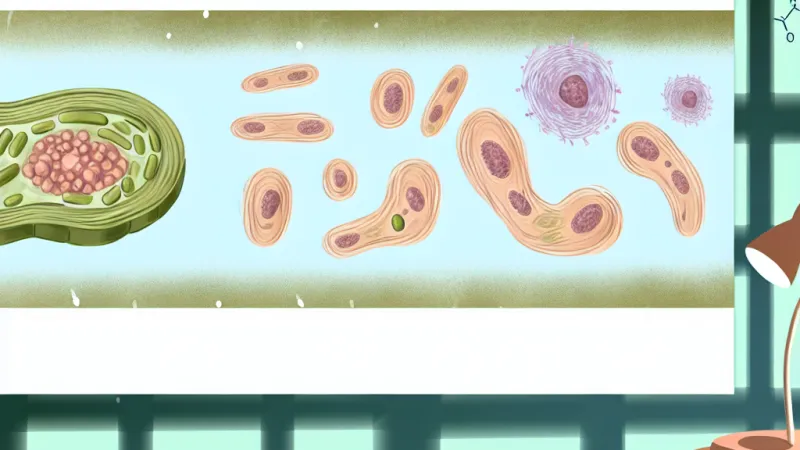

*(For maximum marks, refer to labelled animal and plant cell diagrams alongside this discussion; diagrams and comparative tables summarising cell types offer both visual clarity and exam credit.)*

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in