Religious perspectives on organ transplantation

This work has been verified by our teacher: 17.01.2026 at 14:17

Homework type: Essay

Added: 17.01.2026 at 13:28

Summary:

Explore religious perspectives on organ transplantation and learn how major faiths view donation, ethical dilemmas and UK legal implications for students.

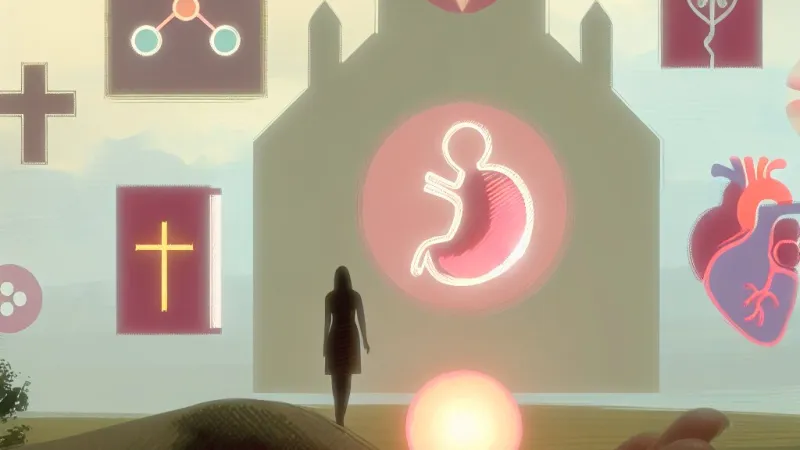

Religious Views Towards Transplant Surgery

Transplant surgery involves the transferring of organs or tissues from one individual to another, either when living (as in kidney donation) or after death (such as heart or corneal transplants). It addresses life-threatening illness and can dramatically enhance quality of life. A “religious view” denotes a perspective derived from doctrinal teachings, ethical codes, or official rulings within a faith tradition, often rooted in scriptures and guided by religious authorities. Religion matters enormously in transplant ethics because it shapes fundamental understandings of the body, moral obligations to others, the afterlife, and authority over life and death. In contexts like the United Kingdom—where medical advances must align with pluralistic values—the dialogue between faith, medical need, and individual rights is especially relevant. This essay will examine several major world religions, exploring both supportive and restrictive attitudes towards transplant surgery. In doing so, it will tease out shared moral themes—such as the imperative to save life and the sanctity of the body—by comparing arguments and discussing their respective strengths and limitations, before arriving at a reasoned conclusion.

Ethical and Legal Frameworks

To engage critically, it is important to identify core ethical concepts that influence religious stances. The “sanctity of life” principle values human existence as inherently sacred; “bodily integrity” stresses the importance of respecting the body in life and death; and “stewardship” is the belief that humans are caretakers, not absolute owners, of their bodies. Meanwhile, altruism and notions of charity, autonomy and consent, and concerns over “playing God” are often cited. There are practical and legal issues as well, including how death is defined (e.g. by cessation of the brain or the heart), the difference between donating as a living person or after death, and systems of consent. Recent legislative changes in England, Wales and Scotland, for example, have made organ donation an “opt-out” system, with implications for religious and personal freedoms.Christian Perspectives

Theological Foundations

Christian teachings place great emphasis on the value of every human life, derived from the biblical conviction that humans are made “in the image of God” (Genesis 1:27). Jesus’ ministry, recorded in the Gospels, was also marked by healings and compassion, underscoring the obligation to alleviate suffering. At the same time, theological debates centre on the nature of bodily resurrection and the unity of body and soul, especially within the Pauline letters (e.g., 1 Corinthians 15).Support for Transplantation

A large number of Christian denominations in the UK, from the Church of England to Methodist and United Reformed traditions, take a more supportive stance. The Church of England’s General Synod has commended organ donation as “a striking example of self-giving love.” Roman Catholic teaching, especially since John Paul II’s statements to the Transplantation Society, supports the principle of donation so long as it is done freely and does not mutilate functional bodily integrity in the case of living donors. Such support is framed in terms of loving one’s neighbour, reflecting the commandment to “love your neighbour as yourself” (Mark 12:31). Many churches actively encourage members to register as donors and to see such a decision as an expression of Christian duty and gratitude towards God.Reservations and Objections

However, reservations do exist. Some Christians, particularly in traditionalist or evangelical circles, raise concerns about maintaining bodily wholeness for the resurrection, citing early Christian burial practices which emphasised respect for the dead. There is also worry that striving to “extend life at any cost” may border on usurping God’s authority over life and death. In certain settings, there may be suspicion towards criteria such as brain death, or concern about the context of donation (for example, if the donor’s lifestyle was “immoral” or the recipients’ needs prioritised above others). Nonetheless, these objections are often countered within Christian thought by the over-riding imperative to save life, and in most UK contexts, mainstream Christian opinion tends towards support, tempered by pastoral care for conscientious objectors.Islamic Perspectives

Core Religious Principles

In Islam, life is regarded as a sacred trust from Allah. The Qur’an holds that “if anyone saves a life, it shall be as though he has saved the lives of all mankind” (Qur’an 5:32), which is foundational to deliberations about transplant surgery. At the same time, bodily integrity both in life and after death is guarded, based on the belief that humans are given their bodies by God to be returned untouched. Islamic law (fiqh) is dynamic, with fatwas given by scholars in response to changing medical knowledge.Support for Transplantation

A number of Islamic scholars and councils, including the Muslim Council of Britain and the UK-based Shaykh Muhammad Imdad Hussain Pirzada, have endorsed organ donation, arguing that the principle of necessity (darurah) allows even normally prohibited acts if they save life. Living donation, provided it does not endanger the donor, is largely accepted, especially when motivated by altruism. Deceased donation is more debated, but has increasingly been permitted if it is not done for profit, violates no burial customs, and occurs with explicit consent from the deceased or their family.Restrictive Views

Nevertheless, other scholars and schools—such as certain Deobandi or Salafi authorities—are more cautious, doubting whether taking organs from the dead is permissible, due to desires for bodily wholeness at resurrection or concerns about desecration. There is also debate over exactly when death has occurred, with some rejecting brain death as sufficient for declaring a person deceased. Therefore, while UK-based Muslim communities often participate in donation, internal divisions and varying advice mean decisions are typically case-by-case.Evaluation

The richness of Islamic legal and ethical tradition allows for flexibility, particularly where necessity is adjudged. Education campaigns and robust legal safeguards around consent and burial practices continue to foster greater confidence among British Muslims.Jewish Perspectives

Obligations and Priorities

Judaism places overriding importance on pikuach nefesh, the obligation to save human life. While respect for the dead (kavod ha-met) and strict burial rituals (halakha) are important—such as the quick, complete burial of the entire body—most rabbinical authorities have concluded that these must be set aside if organs can save another’s life. The Board of Deputies of British Jews, representing mainstream communities, has stated that organ donation is “an act of great merit.”Internal Diversity

However, definitions of death matter. Some Orthodox authorities insist on cardiac death rather than brain death as the proper criterion, in line with halakhic interpretations. More progressive or Masorti (Conservative) rabbis accept brain stem death as sufficient. As a result, there is significant diversity within the community, and those contemplating donation often consult rabbinical advice to ensure all laws are met—even seeking guidance over the precise procedures for removal and burial.Assessment

Generally, the imperative to save life predominates, though concerns about family consent and ritual detail mean the process can be complex.Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism

Hinduism

In Hinduism, beliefs about the body and the soul (atman) influence ethical stances. Donation could attract anxiety about harming the law of karma or disrupting the process of death and rebirth. However, many Hindus point to the duty of selfless giving (seva) and the ideal of compassion as grounds for supporting organ donation, especially when it alleviates suffering. There is also respect for personal autonomy and intention. Practical acceptance varies, and ritual purity or family wishes may play a role in decision-making.Buddhism

For Buddhists, the principle of compassion (karuna) and the wish to relieve the suffering of others underpin support for organ donation. The intention (cetana) behind the act is central; donating a kidney selflessly is encouraged, and Buddhist teachers such as Lama Yeshe have commended such acts. There can be reservations over disturbing the moment of death (which, in some traditions, is considered a critical period), but many see no inherent contradiction between Buddhist ethics and transplantation.Sikhism

Sikh tradition places great store by sewa (selfless service) and the rejection of bodily attachment. The Sikh Council UK, as well as prominent gurdwaras, have promoted organ donation as entirely consistent with religious values. However, decisions remain personal, influenced by family discussions and knowledge of the faith.Secular, Humanist and Pluralistic Approaches

Non-religious perspectives generally centre on autonomy, rational consent, and the utilitarian imperative to maximise overall well-being. In the context of the UK, the NHS’s shift to an opt-out system reflects such reasoning, with a view to saving more lives. Nonetheless, there is savvy awareness of ethical concerns around exploitation, fair allocation, and respect for those who object on conscientious grounds. Humanist organisations embrace organ donation, provided informed consent is robustly protected.Practical and Ethical Crossroads

Consent, Autonomy and Law

Religion interacts with legal frameworks in practice, notably with the current “deemed consent” system in England, Scotland and Wales (while Northern Ireland retains opt-in). Faith groups have sought exemptions for those who object, and the law instructs clinicians to consult families before proceeding. Controversies persist, especially for those with fears over state “overreach” or insufficient publicity about change. For people of faith, clarity around consent and family discussion is seen as crucial to aligning religious values with NHS expectations.Challenges in Medical Definition and Dilemmas

Disagreements over brain death (accepted by most UK law, but not all faiths) impact the willingness of some religious people to permit deceased donation. High-profile cases—such as paediatric donors, or those with stigmatised lifestyles—attract scrutiny from both ethical and religious adjudicators. “Transplant tourism” and organ trafficking raise further challenges, condemned by faith leaders and secular ethicists alike as exploitative and contrary to both compassion and justice.Comparative Analysis

Looking across traditions, there emerge both commonalities and differences. The majority of faiths prioritise life-saving obligations, but also insist on respect for the dead, informed consent, and ritual or legal protections. Abrahamic faiths—Christianity, Islam and Judaism—generally see the saving of life as potentially justifying organ donation, albeit with differing emphases on bodily integrity and resurrection beliefs. Eastern religions focus on compassion, intention, and the wider cosmic effects of one’s actions, with variation according to family or social tradition. Where religious arguments stress dignity, afterlife, and community consent, they may come into tension with the urgent needs to reduce transplant waiting lists; pro-donation readings, whether religious or secular, accentuate love and altruism as decisive. The real strengths of religious perspectives lie in their nuanced attention to meaning, identity, and community; weakness may arise when doctrine does not keep pace with evolving medical practice.Conclusion

Religious traditions contain arguments both for and against transplant surgery and organ donation, with substantial diversity within and across communities. While sacredness of the body, beliefs about the afterlife, and the necessity for ritual observance are often cited in favour of caution, it is clear that most major religions offer strong foundations for supporting transplantation, particularly when motivated by compassion, altruism, and the preservation of life. Given this complexity, it is vital that dialogue between faith communities, health professionals, and legislators continues—ensuring that consent is meaningful, conscientious objection is respected, and advances in medical science sit harmoniously alongside religious conscience. Education, transparency, and respectful engagement are therefore the best paths to reconciling faith and modern medicine in this sensitive field.---

Exam tip: For each religious tradition, root your answer in doctrine, mention key principles, cite real-world practice or official statements, and evaluate internal diversity. In comparisons, use phrases like “in contrast” or “similarly”, and always relate points back to contemporary UK legal frameworks for organ donation. Refer to bodies such as the NHS, Council of Imams and Rabbis, or denominations like the Church of England to show up-to-date awareness. Practice balancing explanation and evaluation for the best grades.

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in