How Experience Shapes Behaviour: The Learning Approach Explained

This work has been verified by our teacher: 24.01.2026 at 4:12

Homework type: Essay

Added: 17.01.2026 at 18:51

Summary:

Explore how experience shapes behaviour with the learning approach; students learn classical conditioning, operant conditioning, SLT, applications and critiques.

The Learning Approach: Exploring How Experience Shapes Behaviour

The learning approach in psychology posits that much of human and animal behaviour is the product of experience, rather than being shaped solely by inherited factors. At its core, it asserts that individuals acquire behaviours through interactions with their environment, guided by mechanisms such as association, consequences, and observation. This essay will examine the main components of the learning approach: classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and social learning theory (SLT), drawing on well-known research from the United Kingdom and beyond. While the approach has provided clear, empirical explanations for the development and modification of behaviour and found practical application in classrooms, therapy, and social policy, it is not without limitations—it often overlooks innate and cognitive influences. A critical evaluation will therefore highlight both strengths and the importance of integration with other perspectives for a fuller understanding of behaviour.

---

Classical Conditioning: Learning by Association

Classical conditioning encapsulates the process by which individuals learn to associate a previously neutral stimulus with a meaningful one, thereby eliciting a similar response. The process involves several key terms: the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) naturally produces an unconditioned response (UCR). By repeatedly pairing a neutral stimulus (NS) with the UCS, the NS becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS), producing a conditioned response (CR).A widely-cited illustration is Pavlov’s experiments with dogs, where a bell (neutral stimulus) was rung before feeding (unconditioned stimulus). Over time, the bell alone (now conditioned stimulus) would cause the dogs to salivate (conditioned response), demonstrating how simple associations can shape reflexive behaviours. In a psychological context, Watson and Rayner’s (1920) "Little Albert" study remains a contentious British-American classic. Here, a young child was conditioned to fear a white rat by pairing its presentation with a loud noise. This experiment starkly demonstrated the potential for phobias to develop through associative learning, with broader implications for understanding anxiety disorders.

In British classrooms, similar mechanisms can arise: for example, a student who is repeatedly embarrassed when answering questions may develop anxiety specifically towards raising their hand in class—a conditioned response to a once-neutral context. Alternatively, advertisers often pair products with uplifting music or attractive imagery, aiming to evoke positive associations in consumers' minds.

Classical conditioning is lauded for its experimental rigour and explanatory power in accounting for rapid acquisition and persistence of conditioned responses. However, its reductionist focus means it struggles to explain complex voluntary or cognitive behaviours. Biological constraints—such as the concept of "preparedness," where certain associations (e.g. snake-fear) form more readily due to evolutionary pressures—limit its generality. Ethical concerns are also evident, particularly in early research such as the Little Albert study, which failed to obtain proper consent or provide adequate protection from harm. Nonetheless, the phenomena of extinction (loss of conditioned response when pairings cease) and spontaneous recovery (reappearance of a conditioned response after time) have robust empirical support and offer measurable predictions.

---

Operant Conditioning: Shaping Behaviour Through Consequences

Operant conditioning, championed by B.F. Skinner, examines how the consequences of an action determine its future likelihood. Behaviours followed by favourable consequences (reinforcement) become more probable, while those followed by adverse outcomes (punishment) diminish.Reinforcement can be positive (adding something pleasant, e.g. praise for homework completed) or negative (removing an unpleasant stimulus, such as abolishing a detention for good behaviour). Conversely, punishment involves introducing negative consequences or removing something desirable. Skinner’s famous operant chamber (or 'Skinner box') experiments with rats and pigeons demonstrated these principles. Animals learned to press levers to receive food rewards, illustrating how reinforcement maintains and strengthens behaviour.

An important refinement involves schedules of reinforcement: behaviours are learned more quickly when reinforcement is frequent, but are more persistent when reinforcement is delivered unpredictably (variable schedules). This is apparent in real-world settings such as classroom token economies—where students earn tokens for positive behaviours, later exchanged for privileges—or through everyday parental strategies, such as restricting or allowing computer time based on behaviour.

Operant conditioning’s scientific strengths are clear: it has produced durable and replicable behaviour modification programmes, especially in schools and psychiatric wards (e.g. token economies in the UK’s NHS settings). However, critics point out its tendency to ignore mental processes, making it somewhat mechanistic. The approach also struggles with individual differences and ethical controversies, particularly when punitive methods are overused or applied to vulnerable populations. Reinforcement schedules, nonetheless, provide insight into the persistence and extinction of behaviours, making the theory highly testable and applicable.

---

Social Learning Theory: Learning by Observing Others

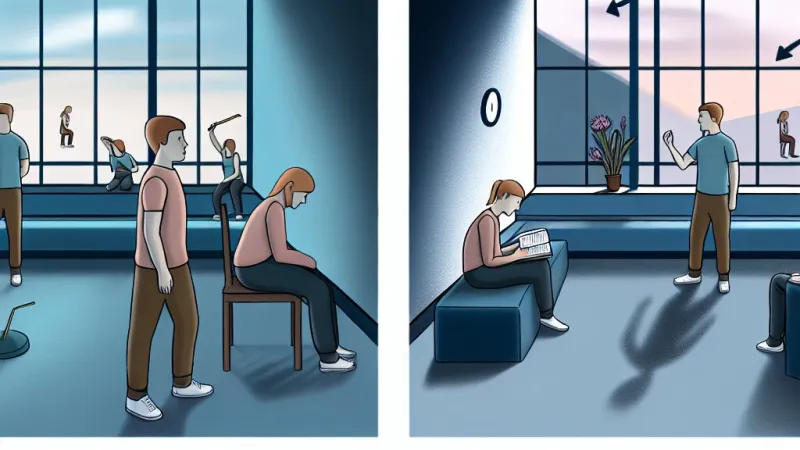

Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (SLT) builds on classical and operant conditioning by suggesting that much learning happens through observing others, rather than through direct experience alone. A key innovation is its inclusion of mediational cognitive processes: one must pay attention, retain the observed behaviour, reproduce it (possessing the ability), and be motivated to imitate—often by observing others being rewarded (vicarious reinforcement).Bandura’s iconic "Bobo doll" experiments, widely discussed in UK psychology classrooms, saw children observe adults behaving aggressively towards a doll. Children subsequently imitated these aggressive behaviours, particularly when they saw the adult being rewarded, underscoring the impact of observed consequences and the role of cognitive appraisal in deciding whether to replicate an action.

SLT is notable for its applicability to a wide range of phenomena: the development of gender-typed behaviour through the observation of family, peers, or teachers; or, in the media context, concerns over the effects of televised violence. The British debate over the impact of media on antisocial behaviour often draws from SLT principles.

SLT’s main strength lies in its integration of cognitive factors with behaviourist principles, offering a more holistic explanation for behaviours that are otherwise unaccounted for by conditioning alone. It adeptly explains learning in the absence of direct reinforcement. Nonetheless, its reliance on laboratory studies, many with artificial tasks, raises concerns about ecological validity. Causality is also harder to establish in observational studies, and it cannot fully explain why certain behaviours are more easily learned than others, hinting at underlying biological predispositions. SLT acts as a crucial bridge between the strict determinism of behaviourism and the growing recognition of cognitive processes.

---

Research Methods in the Learning Approach

The learning approach is grounded in scientific inquiry, employing a mix of controlled laboratory experiments, field trials, and observational studies. Laboratory research (e.g., Pavlov’s or Skinner’s experiments) prioritises control and precision, enabling the establishment of causal relationships and replicability. However, this often comes at the expense of ecological validity—tasks and settings may not mirror real life, limiting generalisability.Structured observations involve coding and tallying pre-defined behaviours within manipulated environments; they provide consistency but can induce artificial responses. Naturalistic observation, by contrast, records behaviour in real-world contexts, increasing external validity but sacrificing control over variables. In all cases, maintaining inter-rater reliability (agreement among observers) is essential, as is minimising observer bias and demand characteristics from participants.

Methodologies such as participant versus non-participant observation, and overt versus covert recording, raise further trade-offs between immersion, objectivity, and ethical considerations. Protected groups—like children—demand special care, requiring informed consent, confidentiality, debriefing and protection from psychological harm, especially in studies involving distressing stimuli as in the Little Albert case.

Ultimately, the methodological sophistication of the learning approach allows for robust, falsifiable hypotheses, but each method entails limitations concerning reliability, validity, and ethical acceptability.

---

The Nature–Nurture Debate and the Learning Approach

The learning approach falls firmly on the "nurture" end of the spectrum, prioritising external experience over innate factors in the explanation of behaviour. Yet, this position has evolved. Modern psychology acknowledges that genes and biology interact with the environment in shaping behaviour. For example, while phobias may be learned via traumatic associations, research (such as Seligman's "preparedness" work) finds that some fears—like those of heights or spiders—emerge more quickly due to evolutionary predispositions. Likewise, a child’s temperament may affect how rapidly or easily they acquire new behaviours.An integrative perspective, therefore, sees the learning approach as offering vital but incomplete insight—a powerful account of how behaviour is sculpted by experience, but ultimately one node in a larger network of explanations.

---

Applications and Real-World Implications

The practical influence of the learning approach is felt across education, clinical psychology, and social policy in the UK. Primary and secondary schools increasingly use positive reinforcement—rewarding praise, merits, and even tangible rewards—to encourage attendance and academic effort. Behaviours are also shaped incrementally ("shaping"), from phonics acquisition in literacy lessons to behaviour contracts for challenging pupils.Clinically, techniques derived from classical and operant principles—including systematic desensitisation and token economies—are used in treating anxiety, phobias, and in managing behaviour within psychiatric hospitals. In the context of criminal justice, behaviour modification strategies underpin many rehabilitation and parenting programmes.

Associations formed in advertising also epitomise classical conditioning at work, while SLT’s emphasis on role models has informed debates on both the influence of televised violence and the importance of teacher behaviour in shaping school ethos.

Despite their efficacy, such interventions require ethical caution—over-reliance on rewards can reduce intrinsic motivation, and punitive strategies are increasingly seen as counterproductive or harmful. Moreover, cultural differences mean certain methods that succeed in one context may falter in another.

---

Strengths and Limitations: A Critical Synthesis

The learning approach’s empirical rigour and practical predictive power are undeniable. Clear, operational definitions and replicable experiments have generated a wealth of evidence and practical interventions—particularly in education and therapy. Its parsimony has led to straightforward explanations and measurable outcomes.However, critics charge that it can be reduced to ‘stimulus in, response out’, neglecting the multifaceted internal world of thoughts, emotions, and motivations. It risks an excess of determinism, downplaying autonomy and intrinsic differences between individuals. The ethical legacy of some early studies and their ecological validity also casts a shadow, while important phenomena—such as the speed with which some behaviours are learned—suggest that biology and cognition must also be considered.

---

Contemporary Directions and Integration

Increasingly, advances in cognitive neuroscience and developmental psychology have spurred a convergence between the learning approach and other fields. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), now standard in NHS mental health services, merges operant principles with the identification and restructuring of thought patterns. Neuroimaging is illuminating the brain’s reward systems and the processes underpinning learning and habit formation.Meanwhile, computational modelling and artificial intelligence increasingly draw on reinforcement learning, helping unravel how both humans and machines adapt to changing environments. Social learning research is also increasingly attentive to cultural influences, developmental stages, and genetic predispositions.

---

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in