Plasma membrane transport: how molecules cross and why it matters

This work has been verified by our teacher: 26.01.2026 at 18:08

Homework type: Essay

Added: 23.01.2026 at 13:39

Summary:

Explore how plasma membrane transport enables molecules to cross cells, understanding the key processes that maintain cell function and life in the UK curriculum.

Exchange Across Plasma Membranes

Every living cell, no matter its role in the body—be it a humble root hair cell in a daffodil or a neuron in the human brain—depends on a delicate boundary: the plasma membrane. This fragile interface between the internal machinery of the cell and its exterior world is not merely a passive shield; instead, it is a highly selective filter, orchestrating the unceasing passage of molecules and ions vital for life. Exchanges across plasma membranes enable a cell to absorb nutrients, expel wastes, regulate water balance, and maintain its intricate internal environment, a process broadly referred to as homeostasis.

Understanding the mechanisms by which substances traverse this membrane is fundamental not only in cell biology but underpins key fields such as physiology, medicine, and biotechnology. This essay explores in depth how exchanges across plasma membranes occur, considering the structure that allows for selective movement, the varied mechanisms—both passive and active—through which molecules and ions cross, and the relevance of these processes in maintaining the life of cells and, by extension, whole organisms.

---

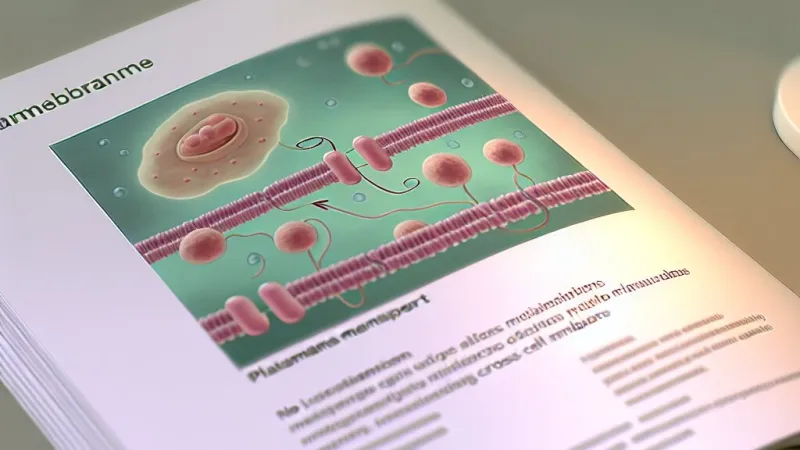

Structure and Properties of the Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane, often described in textbooks as the "fluid mosaic model" devised by Singer and Nicolson (1972), is a double layer of phospholipids interspersed with proteins. Each phospholipid consists of a hydrophilic (water-attracting) "head" and two hydrophobic (water-repelling) "tails". Arranged tail-to-tail, they form a bilayer which is fluid, allowing proteins and lipids to move laterally within the plane—an essential property for the functionality and adaptability of the membrane.Embedded within this sea of lipids are various proteins: some span the bilayer (integral or transmembrane proteins) while others attach only to one surface (peripheral proteins). Channel and carrier proteins provide specific routes for certain molecules or ions, while receptor proteins enable the cell to sense and respond to external signals. Cholesterol molecules dotted amongst the phospholipids add further stability and fluidity, especially important in the fluctuating temperatures typical of the British climate.

The plasma membrane’s most crucial property is its selective permeability: rather than a solid wall, it acts more like the turnstiles of a railway station, allowing some substances through freely while tightly restricting others. Small, non-polar substances such as oxygen and carbon dioxide dissolve easily in the lipid portion and pass unhindered, but large molecules or those with charge often require special passageways. This selectivity underpins every exchange across the plasma membrane.

---

Passive Transport Mechanisms

Diffusion

Diffusion is the most fundamental means by which substances cross the plasma membrane. At its heart, diffusion is the random movement of particles from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration—a process requiring no direct energy input from the cell. For example, oxygen, essential for respiration, moves from the high concentration in alveolar air (in the lungs) into the low concentration in red blood cells, whereas carbon dioxide travels in the reverse direction.Several factors influence the rate of diffusion: the magnitude of the concentration gradient, the temperature (warmer environments increase molecular movement), the size of the diffusing substance, and the thickness and surface area of the membrane. Biological adaptations illustrate these principles: human lungs have a vast surface area and thin alveolar walls to optimise diffusion rates.

Small, lipid-soluble molecules traverse the membrane with ease, but larger or charged substances—like ions or glucose—cannot pass so freely, necessitating other means of transport.

Osmosis

Osmosis is a specialised form of diffusion involving water molecules: it’s the movement of water through a partially permeable membrane from regions of higher water potential (more dilute solution) to lower water potential (more concentrated solution). In biological settings, this determines whether cells swell, shrink, or retain their shape.If plant cells are placed in a very dilute (hypotonic) solution, water enters the cells by osmosis, resulting in turgidity—the cell wall prevents bursting and this turgor pressure maintains plant structure. By contrast, if surrounded by a concentrated (hypertonic) solution, plant cells lose water and plasmolysis may occur, with the cell membrane pulling away from the wall—an event observable in onion epidermal peels, a classic A-level practical. Animal cells, lacking a cell wall, are more vulnerable: red blood cells shrink in hypertonic environments (a process called crenation) or burst in hypotonic ones (haemolysis).

Facilitated Diffusion

Some substances—such as glucose or specific ions—are either too large or too polar to dissolve in the lipid portion of the membrane. Facilitated diffusion provides a way in: transport proteins embedded in the membrane enable these molecules to pass down their concentration gradient. Channel proteins form pores for specific ions, while carrier proteins undergo a conformational change to “ferry” substances across. Notably, this remains a passive process—the cell expends no direct energy.Facilitated diffusion demonstrates exquisite specificity: potassium channels, for example, only allow potassium ions to pass. The rate of facilitated diffusion can reach a maximum if all carrier proteins are occupied, a phenomenon known as saturation, akin to all the checkouts in a supermarket being in use during peak times.

---

Active Transport Mechanisms

Overview and the Role of ATP

Active transport, in stark contrast to passive mechanisms, requires energy—usually in the form of ATP. Here, substances are moved against their concentration gradient, from regions of low concentration to those of high, an uphill battle similar to cycling against the wind.The sodium-potassium pump in animal cells exemplifies this process: it transports sodium ions out of and potassium ions into the cell, both against their respective gradients. This pump underpins essential processes such as nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction; the rapid up-and-down exchange of sodium and potassium generates the electrical signals that allow you to move or think.

Co-Transporters (Secondary Active Transport)

Not all active transport consumes ATP directly. Co-transporters use the energy stored in the concentration gradient of one molecule (often maintained by ATP-driven pumps) to drag another molecule along. In the small intestine, for example, the sodium-glucose co-transporter exploits the sodium gradient to absorb glucose from food even when its concentration is already higher in the intestinal epithelial cells than in the lumen. This ensures not a morsel of precious glucose—a vital energy source—is wasted.---

Example: Glucose Absorption in the Small Intestine

A much-cited example in biology curricula is the absorption of glucose after a meal. Initially, as digested food floods the gut, glucose can enter cells lining the intestine simply by facilitated diffusion—moving down its gradient. However, as the meal is digested and glucose in the lumen drops, a problem emerges: the higher concentration of glucose inside the cells stalls further passive entry.Here, the sodium-potassium pump steps in, actively expelling sodium ions and keeping intracellular sodium levels low. The sodium-glucose co-transporter harnesses the energy from sodium ions moving back into the cell (down their gradient) to simultaneously bring glucose in (against its gradient). Finally, glucose exits into the bloodstream by facilitated diffusion, ready to fuel all manner of bodily processes—from running in the school sports day to revising for A-levels.

---

Factors Affecting Exchange Efficiency

The rate and efficiency of membrane transport rest on several pillars:- Membrane Composition and Availability of Proteins: The number and type of channel and carrier proteins dictate how efficiently substances are exchanged. Epithelial cells in the gut, for instance, possess abundant co-transporters for rapid nutrient uptake. - Environmental Conditions: Temperature and pH can alter both membrane fluidity and protein structure, potentially hindering transport. - Concentration Gradients: Active maintenance of gradients, as seen with the sodium-potassium pump, is essential for continual exchange. - Surface Area and Membrane Thickness: Specialised adaptations like microvilli in intestinal cells increase surface area for absorption, while thinner membranes speed up exchange.

---

Physiological and Clinical Relevance

Efficient and regulated exchange across plasma membranes is foundation to nearly all cellular processes—nutrient uptake, waste removal, nerve impulse conduction, and osmoregulation. Failures in these mechanisms can precipitate disease: cystic fibrosis, prevalent in the UK, is caused by faulty chloride channels, leading to the build-up of thick mucus in the lungs; diabetes arises when glucose transport and uptake become impaired.Targeted manipulation of membrane proteins is a hotbed for medical advancement: many modern medicines are designed to modulate specific transporters, from diuretics acting on kidney tubules to anti-epileptic drugs calming ion flow in neurons.

---

Conclusion

In summary, the plasma membrane is not a static boundary but a dynamic facilitator of cellular life, employing passive and active transport mechanisms to regulate a cell’s internal environment. Through diffusion, osmosis, and facilitated diffusion, cells move substances efficiently and without expending energy; where greater control or uphill movement is required, they harness ATP-powered pumps and co-transporters.These processes are not isolated but work in concert, as beautifully demonstrated in the small intestine’s glucose absorption. Their importance is profound—not only do they form the bedrock of cell biology, but our understanding of them drives medical innovation and reveals the subtle beauty of life’s inner workings. In grasping the complexities of exchange across plasma membranes, we take a step closer to unlocking the secrets of health and disease, with far-reaching implications for medicine, biotechnology, and our understanding of what it means to be alive.

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in