Musculoskeletal and Respiratory Systems: Structure, Function and Control

This work has been verified by our teacher: 17.01.2026 at 9:44

Homework type: Essay

Added: 17.01.2026 at 9:26

Summary:

Understand musculoskeletal and respiratory systems: learn structure, function and control, cellular mechanisms, training adaptations and clinical relevance.

Anatomy and Physiology: Structure, Control and Adaptation of the Human Musculoskeletal and Respiratory Systems

Anatomy and physiology are intimately woven disciplines concerned with the form and function of the human body. In the context of movement and gas exchange, these fields provide essential frameworks for understanding the remarkable capabilities and limitations of the body, from the microscopic machinery of muscle contraction to the orchestration of breathing during intense exercise. This essay will explore the cellular and molecular underpinnings of muscle function and respiratory mechanics, emphasising how structural specialisations at every level enable efficient force generation and gas exchange. It will also discuss how these attributes are coordinated through neural and chemical control, how they adapt with training and disease, and why such knowledge is vital to fields as diverse as sport, medicine and public health. The discussion will be structured in five main parts: (1) the biochemical and cellular basis of muscle work; (2) classification and recruitment of muscle fibres; (3) mechanisms of muscle contraction; (4) the mechanics and control of ventilation; and (5) integration with the cardiovascular system, including practical and clinical applications. The scope is focused specifically on skeletal muscle and pulmonary ventilation, using examples relevant to British athletic, health and educational contexts.

---

Cellular and Biochemical Foundations of Muscle Function

At its core, muscle function is a question of energy — how quickly and efficiently a muscle fibre can generate and replenish Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP), the molecular currency of work. Various structural and biochemical features of muscle cells enable this.Mitochondria, for instance, are abundant in muscle fibres that rely upon long-duration, low-intensity activity. These “powerhouses” are packed within slow-twitch fibres and enable sustained ATP synthesis via oxidative phosphorylation, utilising both fats and carbohydrates in the presence of oxygen. Endurance athletes such as marathon runners or Tour of Britain cyclists display markedly higher mitochondrial densities, a fact reflected in their resistance to fatigue.

Myoglobin is another key protein, serving as an oxygen store within muscle fibres. Its crimson tint betrays its presence, particularly within muscles rich in slow-twitch fibres, as in the postural muscles of the back. Myoglobin facilitates the rapid diffusion of oxygen from blood capillaries deep into the cell, thereby supporting aerobic metabolism during sustained effort.

For rapid, high-intensity exertion — think of the explosive acceleration of a 100m sprinter or the swift catch-up in a rugby dash — muscles use the phosphocreatine (PCr) system. PCr provides a near-instantaneous source of phosphate to regenerate ATP, but is swiftly depleted, being optimally suited to efforts lasting only a few seconds.

Glycogen reserves within muscle, meanwhile, serve as a localised carbohydrate store, fuelling energy needs through anaerobic glycolysis. This pathway, used during efforts such as indoor rowing sprint events or the final laps of the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race, generates ATP quickly but at the cost of lactate accumulation and limited duration.

Critical to all these metabolic processes is the capillary network surrounding each fibre. The density of capillaries governs the ease with which oxygen, glucose and other metabolites can reach, and waste products be removed from, muscle cells. In young, fit individuals, regular endurance training increases capillarisation, expediting both performance and recovery.

Time Course of Energy Systems: During a 100m sprint, the PCr system dominates for the first 6-10 seconds; as the effort continues into the 400–800m middle distance, anaerobic glycolysis takes precedence, while events like a 5k run draw increasingly on aerobic, mitochondrial ATP production. Diagrams or graphs illustrating this shifting dominance, as taught in A-level PE courses, reinforce understanding of this dynamic interplay across sports.

---

Muscle Fibre Types and Recruitment

Skeletal muscles are far from uniform. Each contains a mosaic of fibres, each with distinct architectures and metabolic strategies shaped by evolution and, as we now know, by patterns of use and training.Type I (Slow Oxidative) Fibres: Structurally, these fibres are relatively small and densely packed with mitochondria, boasting a web of adjacent capillaries and a high concentration of myoglobin. Their principal source of ATP is aerobic metabolism, rendering them superbly resistant to fatigue. Such attributes make them central to postural maintenance and endurance sports. An illustrative example is Mo Farah’s running form: his muscles are tailored for hours of steady, repetitive contractions with minimal loss in force.

Type IIa (Fast Oxidative-Glycolytic) Fibres: These intermediary fibres feature greater diameter than Type Is, a healthy supply of mitochondria, more moderate capillarisation, and elevated glycolytic enzyme content. Functionally, they bridge the gap, being capable of both aerobic and anaerobic ATP generation. They deliver moderately sustained power at high rates — ideal for events like the 800m or 1,500m middle distance, or the rapid, repeated bursts of a hockey match. Notably, these fibres are particularly trainable: endurance work can shift their characteristics towards greater oxidative potential.

Type IIx (Fast Glycolytic) Fibres: The largest of the group, Type IIx fibres contain scant mitochondria and myoglobin, but store considerable glycogen and PCr. These 'white' fibres are capable of extraordinary force and speed, excelling in events such as Olympic weightlifting or the opening yards off the starting blocks in swimming. They fatigue rapidly, however, making them ill-suited for prolonged activity but ideal for maximal, short-lived exertion.

The classic studies of muscle biopsies from Olympic rowers, conducted at UK Sport Labs, illustrate how elite athletes in strength versus endurance disciplines differ markedly in their fibre compositions.

Motor Units and Recruitment Strategy: A motor unit consists of a single lower motor neuron and all the muscle fibres it stimulates. The neurologist Elwood Henneman described how the recruitment of these units is hierarchical. For gentle, precise tasks — such as holding a violin bow — the brain activates small motor units composed mainly of slow fibres. As force requirements increase, progressively larger motor units, often rich in fast fibres, are engaged. This systematic activation, described as the "size principle", allows for fine gradations of force and energy efficiency.

Activation of muscle involves an orchestrated sequence: an action potential sweeps down the nerve, acetylcholine is released at the neuromuscular junction, and, provided the signal surpasses a threshold, all fibres in the motor unit respond together (the all-or-nothing phenomenon). In whole muscles, force can be modulated by increasing the number of units recruited (recruitment), how rapidly they fire (rate coding), and the synchrony among them.

Such neurological coordination underpins feats as varied as the sustained squat of a rower on the Thames or the rapid, powerful movements seen in professional footballers. Clinical cases — such as the impaired recruitment seen in motor neurone disease or after stroke — further highlight the relevance to health and rehabilitation.

---

Mechanism of Muscle Contraction

The translation of nervous command into visible movement — known as excitation–contraction coupling — is grounded in a series of molecular events within muscle fibres.The sliding filament theory, first evidenced by A.F. Huxley at Cambridge in the 1950s, proposes that contraction results from the sliding of thin (actin) filaments past thick (myosin) filaments within the fundamental structural unit, the sarcomere. Force production relies critically on ATP and calcium ions.

Sequence of Events in Excitation–Contraction Coupling:

1. Nerve Action Potential: Arrives at the neuromuscular junction, prompting the release of acetylcholine into the synaptic cleft. 2. Muscle Action Potential: Acetylcholine binds receptors, depolarising the sarcolemma (muscle membrane), with the signal quickly propagating along T-tubules. 3. Calcium Release: This electrical signal triggers the sarcoplasmic reticulum to release calcium ions. 4. Bridge Formation: Calcium binds to troponin, shifting tropomyosin and exposing binding sites on actin. Myosin heads attach, perform a power stroke (powered by ATP hydrolysis), and subsequently release when another ATP molecule binds. 5. Relaxation: Calcium is pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and the contractile machinery resets.

Fast-twitch fibres boast a more elaborate sarcoplasmic reticulum and faster calcium cycling proteins than slow-twitch fibres, enabling brisk shortening and relaxation. By contrast, the greater mitochondrial content of slow fibres underpins their endurance rather than speed.

Diagrams displaying a labelled sarcomere, with attention to actin-myosin interaction, Z-lines, and the ATP/calcium pathways, assist in visualising these molecular mechanisms.

---

Respiratory Mechanics and Control

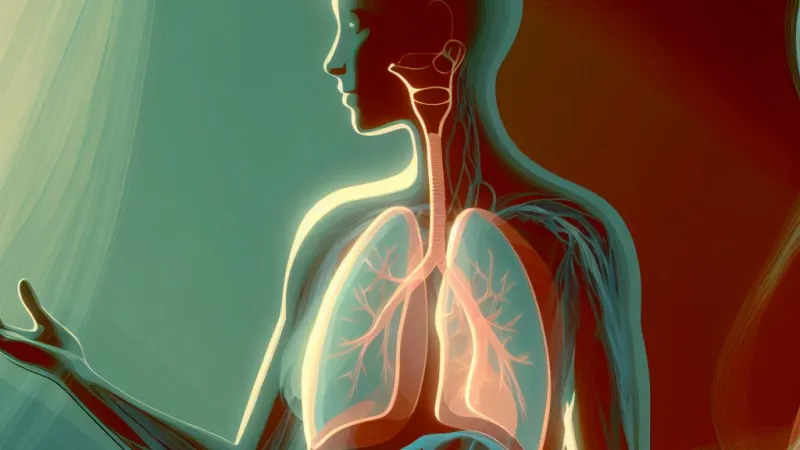

Efficient movement demands an equally efficient system for oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal. Breathing is the bridge between the external environment and the muscle's internal combustion.Mechanics of Ventilation: At rest, inspiration is primarily the domain of the diaphragm, which, when contracted, flattens and increases thoracic volume, lowering pulmonary pressure and drawing air in. Assisting are the external intercostal muscles, lifting the ribcage gently. Expiration at rest is passive, reliant on elastic recoil.

During exercise, additional muscles assist. The sternocleidomastoids and scalenes elevate the ribcage further, whilst active expiration recruits internal intercostals and the abdominal wall to forcefully expel air, as seen in strenuous sports or wind instrument performance. This dynamic increase in thoracic volume and pressure changes supports the surge in oxygen demand (see Figure 4).

Relevant volumes measured include tidal volume (the amount inhaled/exhaled per breath), vital capacity (maximum exchangeable air), and minute ventilation (total air moved per minute). All rise during exercise: for instance, during a netball match, an athlete’s breathing rate and depth both increase substantially to meet metabolic demand.

Neural and Chemical Control: The rhythm of breathing is regulated via centres in the medulla oblongata and pons, which integrate sensory inputs. Central chemoreceptors (sensitive to CO2 and pH) and peripheral chemoreceptors (monitoring blood O2, found in the carotid and aortic bodies) fine-tune breathing frequency and depth. When exercising, rising CO2 and hydrogen ion levels — as seen during a six-minute Cooper test run — stimulate increased ventilation. Mechanoreceptors in joints and muscles, as well as cerebral commands (feedforward mechanisms), also contribute to anticipatory rise in ventilation.

Understanding these controls explains everyday experiences, such as the urge to breathe during voluntary breath-holding, or the hyperventilation seen in panic attacks. Clinically, knowledge underpins the management of conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and guides therapeutic interventions in respiratory physiotherapy.

---

Integration with the Cardiovascular System and Practical Implications

Optimal athletic performance and basic daily function both hinge upon the integration of muscular, respiratory and cardiovascular systems to deliver and utilise oxygen effectively.The oxygen transport cascade begins with atmospheric intake, traverses alveolar membranes into blood, and is carried via haemoglobin through the arterial system — propelled by cardiac output — to distant working muscles. Oxygen then diffuses into muscle fibres, eventually entering mitochondria for ATP production. This relationship is summarised by the Fick principle: oxygen consumption is determined by both the volume of blood delivered and the difference in oxygen content between arteries and veins.

Training Adaptations are highly specific. Endurance training, as seen in distance runners or triathletes, increases capillary density, mitochondrial numbers, oxidative enzyme activities, and cardiac stroke volume. Muscles thus become more efficient and fatigue-resistant. Strength and power training, prioritised by sprinters and weightlifters, drives increases in fibre cross-sectional area, PCr and glycogen stores, and enhances neural recruitment. These adaptations, however, are not absolutely fixed — with appropriate stimulus, muscle fibres can shift towards more oxidative or more glycolytic characteristics.

Such knowledge transfers into clinical settings, where, for example, exercise-based rehabilitation supports patients with respiratory muscle weakness or cardiovascular disease, highlighting exercise prescription as a tool for both prevention and therapy.

---

Evaluation, Limitations and Future Directions

Although the classification of muscle fibre types is a valuable teaching framework, real muscle tissues present a spectrum rather than discrete categories, with hybrids and adaptive shifts shaped by training, disuse, ageing and even genetic predisposition. Most insights into muscle function derive from invasive biopsies, often in specialised or clinical populations, and might not account for the full complexity seen in living, intact humans. Future advances may come through the application of non-invasive imaging, genetic profiling and large-scale, longitudinal studies observing adaptation in real-world settings.---

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in