Diffusion, Osmosis and Active Transport: Biology Unit 3 Summary

This work has been verified by our teacher: 25.01.2026 at 13:27

Homework type: Summary

Added: 24.01.2026 at 13:59

Summary:

Explore diffusion, osmosis, and active transport to understand how substances move in cells. Master key Biology Unit 3 concepts for GCSE success.

Biology Unit 3 Notes: A Comprehensive Overview of Exchange Processes and Transport Mechanisms

Introduction

The marvel of life depends upon the constant movement of substances between cells and their environment. Whether it is the absorption of oxygen for respiration, the uptake of water by a plant’s roots, or rehydration after a strenuous session of football on a misty English morning, the mechanisms that drive these exchanges are nothing short of remarkable. Biological exchange and transport processes form the very scaffold upon which living organisms survive, adapt, and thrive. Within human and plant systems alike, the transport of gases, nutrients, water, and ions underpins everything from cellular health to elite sporting performance. This essay seeks to unravel the intricate choreography of biological transport—exploring diffusion, osmosis, and active transport, examining the specialised surfaces enabling these processes in both humans and plants, and considering their practical implications such as artificial breathing aids and effective hydration. Through a lens attuned to the United Kingdom’s educational and cultural context, these fundamental concepts will be explored not only as GCSE requirements but also as phenomena that influence our everyday lives.---

Biological Transport Mechanisms

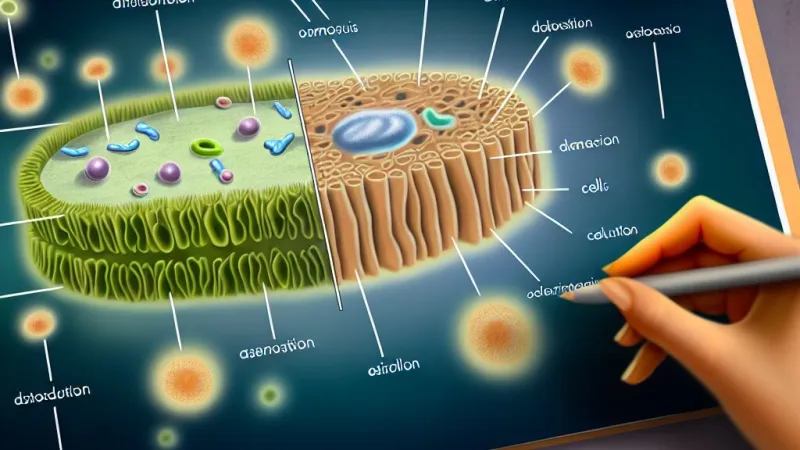

Diffusion

At the heart of biological exchange lies diffusion: the passive movement of particles from a region of higher concentration to one of lower concentration, propelled not by cellular effort but simply the random, kinetic energy of molecules. A classic British classroom demonstration often involves perfume or potassium permanganate crystals diffusing through water; students watch as colour or scent gradually fills the available space. In living organisms, diffusion enables vital gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide to traverse the cell membrane. For instance, in the red blood cells circulating through our arteries and veins, oxygen enters by diffusion—a process determined by factors including the steepness of the concentration gradient, the temperature of the environment (a hot summer’s day will see reactions speed up), the surface area available for diffusion, and the distance particles must travel. Shorter distances, such as those provided by the thin walls of human alveoli, ensure rapid and effective exchange. Without diffusion, cells would be starved of oxygen and nutrients and overwhelmed by waste, bringing life to a grinding halt.Osmosis

Distinct from diffusion due to its specificity for water, osmosis refers to the movement of water molecules across a partially permeable membrane—one which allows some particles through but not others. Water moves from a region of higher water potential (a more dilute solution) to one of lower water potential (a more concentrated solution), an action beautifully illustrated when celery stalks are placed in dyed water. Osmosis is pivotal for maintaining the integrity of cells; animal cells may swell or burst if too much water enters, while plant cells become turgid, supporting upright growth in everything from dandelions to great English oaks. In mammals, osmosis governs water reabsorption in the kidneys—a process essential for conserving water and maintaining electrolyte balance, particularly during physical activities or when challenged by British weather, with its characteristic unpredictability.Active Transport

Unlike diffusion and osmosis, active transport requires energy—specifically, ATP produced through cellular respiration. Active transport moves molecules against their concentration gradient, from a region of lower to higher concentration. This is achieved via specific carrier proteins within the cell membrane, effectively pumping essential nutrients and ions into or out of the cell. Notable examples in human physiology include the reabsorption of glucose from filtrate in the kidney tubules—a process that ensures precious energy is not lost in urine—and the uptake of mineral ions like nitrates from the soil by plant roots, crucial for protein synthesis and healthy plant growth. In nerve transmission, active transport of sodium and potassium ions establishes the gradients necessary for nerve impulses, underpinning everything from basic movement to complex thought.---

Human Exchange Surfaces and Their Function

Gas Exchange in the Lungs

Human beings, as large and complex multicellular organisms, require highly specialised exchange surfaces to meet their metabolic demands. The lungs are perhaps the most iconic of these, their labyrinth of bronchioles ending in millions of alveoli—tiny, balloon-like sacs providing an enormous surface area within the chest. Each alveolus is encased in a dense capillary network, and the walls are remarkably thin—just a single cell thick—ensuring minimal distance for gases to travel. As we inhale fresh air, oxygen moves down its concentration gradient into the blood, while carbon dioxide, produced by respiration, diffuses out to be expelled. The constant movement of air in and out of the lungs—a process sustained by breathing—keeps the concentration gradients steep, enabling efficient, ongoing gas exchange. When considering lung health, such as in patients with emphysema (a condition sadly common amongst British ex-smokers), destruction of alveoli walls drastically reduces surface area, impairing oxygen uptake and leading to breathlessness.Mechanism of Ventilation in Breathing

Ventilation, or the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs, is driven by the coordinated action of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles. During inhalation, these muscles contract, expanding the thoracic cavity and decreasing pressure within the lungs, causing air to rush in—much as opening a window on a chilly morning lets fresh air flood into a room. In exhalation, the muscles relax, the thoracic volume diminishes, pressure rises, and air is expelled. This rhythmic action maintains the concentration gradients essential for diffusion, allowing our bodies to respond to changes in demand—such as sprinting for a late bus in the rain or quietly reading in the school library.Artificial Breathing Aids

Modern medicine in the UK, exemplified by the NHS, has seen the introduction and evolution of various artificial breathing aids. Pioneering negative pressure devices, like the “iron lung” used during post-war polio outbreaks, encased patients’ bodies, creating pressure changes to ‘breathe’ for those with paralysed muscles. Contemporary positive pressure devices—ranging from simple CPAP machines for sleep apnoea to advanced hospital ventilators—deliver air directly to the lungs, supporting patients undergoing surgery or suffering from severe respiratory illness, including Covid-19 during recent years. The progression from cumbersome, mechanical devices to sleek, computer-controlled ventilators illustrates the ingenuity and adaptability of medical science.Absorption in the Digestive System

Beyond the lungs, the small intestine represents another critical exchange surface, responsible for the absorption of digested food molecules. Here, the inner lining is elaborately folded into countless villi—finger-like projections bristling with microvilli on their surface, magnifying the surface area dramatically. Over every square centimetre, a rich blood supply awaits to whisk away absorbed nutrients like glucose and amino acids, delivered mostly by diffusion but, for certain molecules, by active transport. The thin epithelial layer—just one cell deep—shortens the journey for every nutrient molecule, ensuring a swift and efficient process. The importance of this system is evident when it fails; conditions like coeliac disease, relatively prevalent in the UK, can flatten the villi, reducing absorption and leading to nutritional deficiencies.---

Exchange Processes in Plants

Gas Exchange through Leaves

Plants, from humble clover to the stately sycamore, require effective gas exchange for survival. Leaves serve as the principal sites, their lower surfaces punctuated by stomata—small, regulated openings bordered by guard cells. During daylight, stomata often open to allow carbon dioxide in for photosynthesis while oxygen, the photosynthetic by-product, and water vapour exit. At night or during water shortage, the guard cells close the stomata to prevent excessive water loss. Environmental factors typical of UK climate—light intensity, humidity, and atmospheric CO₂ levels—fine-tune these responses, helping plants balance gas exchange with water conservation. This dynamic is visible in wilting plants during summer scorchers or rapid stomatal closure during sudden drought.Water Loss via Transpiration

Transpiration, the evaporation of water from plant leaves through stomata, facilitates the upward movement of water (and dissolved minerals) from soil to leaf—a process vital for survival and growth. While transpiration cools plants during hot spells and ensures the transport of essential ions, unchecked water loss can be fatal. Plant adaptations abound: many UK plants possess a waxy cuticle to slow evaporation, or alter leaf orientation to reduce exposure. During crisp, dry days, stomata may close, preserving water, though at the cost of slower photosynthesis. The thinness and flatness of typical British leaves, from beech to bramble, ensure minimal diffusion distances and thus high efficiency of gas exchange.---

Practical Applications Related to Biological Exchange

Sports Drinks and Hydration

Anyone who has played Sunday league football or completed the London Marathon knows first-hand the effects of strenuous exercise: fast breathing, profuse sweating, and an insistent thirst. Physical activity increases muscle metabolism, boosting oxygen and glucose demands and resulting in significant fluid and ion loss through sweat. Sports drinks, familiar sights on the pitch or in gyms, are formulated to replace both water and essential ions like sodium and potassium, as well as glucose to replenish energy. Isotonic drinks are particularly popular as they match the concentration of solutes in our body fluids, ensuring rapid absorption without upsetting the delicate osmotic balance. Proper hydration maintains performance and supports recovery, a topic of ongoing research and significance for athletes across the United Kingdom.Relevance of Biological Transport Knowledge in Medicine and Physiology

A deeper understanding of biological exchange has direct impacts on healthcare. The management of conditions like cystic fibrosis, which disrupts mucus and the exchange of gases in the lungs, depends upon knowledge of these fundamental processes. The design of medical devices—for instance, the ventilators that became lifelines during the recent pandemic—rests upon principles of human respiration and gas exchange. Similarly, nutritional recommendations for rehydration, whether following diarrhoea or heatstroke, are based on restoring lost electrolytes and water through optimally balanced solutions, embodying the same physiological principles taught in GCSE Biology.---

Conclusion

In sum, the movement of substances across membranes and specialised surfaces, via diffusion, osmosis, or active transport, constitutes the foundation for all life processes. Both plants and humans are shaped, inside and out, by the structures that maximise exchange—be it the tiny alveoli in our lungs, villi in our intestines, or stomata in the leaves above our heads. The practical applications, from sports nutrition to respiratory therapy, illustrate how an understanding of these processes transcends the classroom, improving well-being and tackling real-world challenges. As we continue to face new health and environmental questions, an appreciation of these elegant biological mechanisms equips us not only to understand life but to sustain and enhance it in the worlds of science, sport, and everyday living.Frequently Asked Questions about AI Learning

Answers curated by our team of academic experts

What is diffusion in biology unit 3 summary notes?

Diffusion is the passive movement of particles from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. This process does not require energy and allows essential gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide to move across cell membranes.

How does osmosis differ from diffusion in biology unit 3 summary?

Osmosis specifically involves the movement of water molecules across a partially permeable membrane from high to low water potential. Diffusion can involve any particles, while osmosis is only for water.

What is active transport in the biology unit 3 summary?

Active transport is the movement of molecules against their concentration gradient using energy from ATP. It uses carrier proteins to transport essential nutrients and ions into or out of cells.

What factors affect diffusion explained in biology unit 3 summary?

Diffusion is affected by the concentration gradient, temperature, surface area, and the distance molecules travel. Shorter distances and larger surface areas speed up the process.

Why are osmosis and active transport important in biology unit 3 summary?

Osmosis maintains cell integrity and water balance, while active transport ensures the absorption of vital nutrients like glucose and mineral ions. Both processes are critical for healthy cell and organism function.

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in