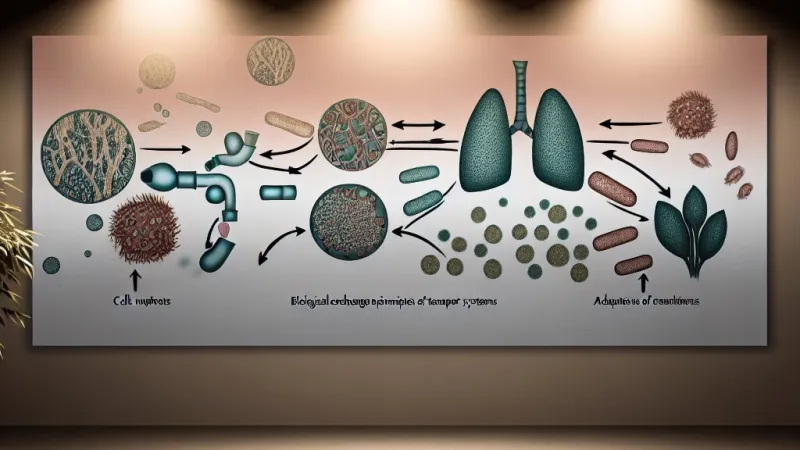

Biological exchange: principles and adaptations of transport systems

This work has been verified by our teacher: 17.01.2026 at 12:32

Homework type: Essay

Added: 17.01.2026 at 11:56

Summary:

Explore biological exchange principles and adaptations of transport systems to learn how surfaces and gradients enable gas, nutrient and water exchange.

Exchange: Principles and Adaptations of Biological Exchange Systems

Introduction: The Necessity of Exchange in Living Organisms

Biological exchange, in its simplest sense, refers to the transfer of gases, nutrients, water, ions and metabolic wastes between an organism and its environment, or between internal compartments. From the humble amoeba drifting in a pond to the complexity of the human respiratory system, this fundamental process lies at the heart of life. However, as organisms increased in both size and structural sophistication through evolution, the challenge of effective exchange has grown. Simple diffusion across an entire surface, sufficient for the microscopic world, rapidly becomes inadequate. Consequently, a variety of ingenious adaptations have emerged, each shaped by underlying physical laws and environmental constraints. This essay investigates the universal problems posed by exchange, discusses the general strategies organisms employ to solve them, and critically examines a selection of model systems—including unicellular organisms, insects, fish, plants, and mammals. These examples will be woven together, highlighting both their shared principles and unique solutions, to elucidate how life overcame the limitations of exchange in its many forms. Ultimately, the design of exchange surfaces embodies a continuous balancing act—maximising efficiency while minimising risks of water loss, infection, or mechanical damage.Foundational Principles and the Framework of Exchange

At the most basic level, movement of substances such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nutrients depends on diffusion—driven by differences in concentration (for solutes) or partial pressure (for gases). The speed of this process can be summarised by the following proportionality: the rate of diffusion increases with a larger exchange surface area and a steeper concentration gradient, but decreases as the diffusion path becomes longer. While this can be mathematically formalised by Fick’s Law, the essential logic for biological purposes is intuitive: greater area and gradient enhance exchange, thicker barriers impede it.The properties of the medium play a crucial role. In air, gases diffuse approximately ten thousand times faster than they do in water; aquatic organisms thus wrestle with the dual limitations of oxygen’s low solubility and slow movement, driving specific adaptations in structure and behaviour.

Yet, diffusion alone is not enough; gradients must be maintained. For a gradient to persist, an organism must either continuously remove substances from the receiving side (as with oxygen in blood) or replenish them at the source (as with oxygenation of water over gills). Cellular respiration and metabolic consumption help by lowering local concentrations, while larger-scale mechanisms—such as blood circulation or ventilation—refresh the environment near the exchange surface.

Across kingdoms, all living things strive to solve similar problems: how to expose sufficient surface for exchange without excessive water loss or vulnerability; how to keep diffusion distances minimal; and how to efficiently distribute substances throughout their internal volume.

Adaptations of Exchange Systems: Structural and Functional Overview

Large Effective Surface Area

Biological innovation has led to numerous ways of amplifying the effective area over which exchange can take place. For instance, within the lungs, the membrane area formed by the alveoli is over fifty times that of the external body surface. Gill lamellae, villi in the gut, and the intimal surface of capillaries are other examples where folding and microanatomy deliver huge area in compact volumes.Short Diffusion Distances

Efficient exchange demands minimal thickness between the two environments. Alveolar and capillary walls in mammals are just one cell thick; gill lamellae are wafer-thin; most active exchange surfaces share this trait. At the ultrastructural level, thin membranes and reduced extracellular spaces promote speedy diffusion.Selective Permeability and Surface Chemistry

Living membranes possess a suite of protein channels and transporters, ensuring that only appropriate substances cross. Chemical modifications, such as surfactant in the lungs or mucus on plant and animal surfaces, further fine-tune permeability and prevent collapse or water loss.Maintaining Gradients

Organisms employ bulk flow mechanisms (such as breathing or circulatory pumping) and active transport (powered by ATP) to sustain the gradients upon which diffusion depends. Without these, equilibrium would soon be reached and exchange would grind to a halt.Protective and Regulatory Features

Exposure brings risks. Valves, such as spiracles in insects or stomata in plants, regulate opening and closing; waxy cuticles, ciliated epithelia, and immune cells provide further layers of defence. Meanwhile, many exchange organs are internalised, thus sheltering delicate structures from external hazards.Internal Transport Integration

Exchange surfaces must be functionally linked to internal delivery systems—blood, lymph, haemolymph or specialised tubes—ensuring that resources reach all parts of a large organism at the required speed.Case Studies Across the Tree of Life

A. Unicellular Organisms: Simplicity and Limitation

Unicellular beings such as amoeba and bacteria rely on a single, flexible membrane as the interface with their environment. Their metabolic demands are modest, and crucially, every part of their small volume (often just a few micrometres across) lies near enough to the surface that diffusion alone suffices. No cell organelle is far from the outside world, so oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, and wastes flow in and out directly, following the gradient set by intracellular consumption and external supply.Yet, this approach does not scale. As a cell grows, its volume increases more rapidly than its surface area—thus the surface area:volume ratio shrinks, and diffusion can no longer meet the needs of metabolism. This fundamental geometric constraint is one factor propelling the evolution of multicellularity and specialisation.

B. Insects and the Tracheal System: Direct Airway Delivery

Insects represent a remarkable adaptation: the tracheal system. Air enters through paired spiracles—shielded by valves that respond to humidity, CO2 levels, or threat—and travels through branching tubes that ramify throughout the entire body. The smallest branches, tracheoles, reach almost every cell, bringing atmospheric oxygen within micrometres of mitochondria.Exchange at the terminal tracheole occurs by diffusion, maximised by the minimal path length and the gaseous state of the medium. During periods of high demand, muscle movements or body pumping create a convective airflow, enhancing supply; at rest, passive diffusion is sufficient.

Water loss is a perennial risk for terrestrial insects. The tracheal tubes are lined by a waterproof cuticle, and spiracle closing can achieve near-complete water retention for short periods. Some desert insects time their spiracle openings to coincide with drought-resistant phases, or minimise exposure by clustering spiracles or keeping them shaded.

Under extreme activity (such as flight in dragonflies), absorption of tracheal fluid into muscles shortens the diffusion path further, meeting the surging O2 demand. This interplay of structure, behaviour and physiology typifies evolutionary problem-solving.

*A labelled sketch of the tracheal system, showing spiracles, branching tracheae, and fine-ended tracheoles, would be valuable here.*

C. Aquatic Vertebrates: Gills and Countercurrent Flow

Fish face the twin challenges of low oxygen solubility and slow aquatic diffusion. Their solution is the gill: composed of thin filaments bearing hundreds of microscopic lamellae, together providing vast surface area. What sets aquatic exchange apart is the countercurrent system: water and blood flow in opposite directions across the gill lamellae. This arrangement ensures that the oxygen gradient is maintained at every point along the capillary—maximising transfer efficiency.Water is driven across the gills by coordinated movements of mouth and operculum (gill cover), generating a directed flow. In parallel, blood capillaries within the lamellae carry deoxygenated blood into the region with the highest water-oxygen content, and sweep it away as it is loaded with O2.

As water contains only about 1/20th as much oxygen as the same volume of air (at standard temperature and pressure), the overall energy costs are higher, and flow rates must be adjusted accordingly. Fish thus exemplify how physical laws determine organ structure.

*A helpful diagram here would show water flowing in one direction across a lamella, with blood flowing oppositely—the countercurrent arrangement.*

D. Plant Leaves: Photosynthesis and Gas Exchange

Plants, especially leaves, exhibit a sophisticated balance between gas uptake/release and water conservation. Their outer surfaces are usually covered in a waterproof cuticle, yet they bear pores—stomata—guarded by pairs of responsive guard cells. These open and close to admit CO2 for photosynthesis and release O2, while minimising water loss. Internal air spaces in the mesophyll connect to all stomata, ensuring gases can diffuse rapidly to every photosynthesising cell.The stomata open in response to daylight (driven by blue light perception and guard cell turgor), low internal CO2, and humidity; closure is triggered by abscisic acid during drought stress or darkness. Xerophytes—plants adapted for dry environments—show additional features: sunken stomata, thick cuticles, hairy or rolled leaves, and even biochemical strategies (like CAM and C4 pathways) that temporally or spatially separate water loss from carbon fixation.

*An illustration showing a cross-section of a leaf, with details of the stomata, air spaces, and mesophyll, would clarify these relationships.*

E. Mammalian Lungs: Complexity in Air Breath

Humans and other mammals rely on highly branched lungs ending in millions of alveoli—microscopic sacs with incredibly thin walls closely wrapped in a capillary network. The lung structure multiplies exchange area to an astonishing 70–100 square metres in humans, while keeping the alveolar-capillary membrane at about 0.3 micrometres thick.Ventilation is achieved via the muscular diaphragm and rib cage, creating negative pressure and drawing fresh air into the alveoli. Here, oxygen diffuses across the surfactant-coated lining and thin epithelium into the blood, which is then whisked away by red cells loaded with haemoglobin. The presence of surfactant is vital: it keeps alveoli from collapsing, preserves surface area, and helps maintain even gas exchange.

Pathology exposes the delicate optimisation at work: as seen in emphysema (where surface area is destroyed), pulmonary fibrosis (where the membrane thickens), or oedema (fluid accumulation), any loss of area or increase in thickness has dramatic effects on exchange.

*A simplified diagram of an alveolus with capillary, showing the thin barrier, surfactant layer, and red cell would benefit understanding.*

Comparative Analysis: Similar Problems, Divergent Solutions

Across kingdoms and environments, organisms have hit upon strikingly parallel strategies to the problem of exchange. Small organisms trust to diffusion, exploiting high surface area:volume ratios. Larger beings internalise and amplify their exchange surfaces—invaginations (lungs), evaginations (gills), or internalised infoldings (tracheae). The medium shapes design: air breathers can afford large areas; aquatic organisms favour thin, highly folded membranes and countercurrent blood flow. Behaviour, such as active ventilation, and structure, like branching or folding, are often integrated.Yet, every solution brings costs: water loss in plants and insects, the energetic burden of pumping in fish and mammals, or physical vulnerability when surfaces are too exposed. Some systems, such as the direct delivery of O2 in insects, are fantastically efficient but put a cap on maximum organism size; others, like the mammalian lung-blood circuit, permit large and active bodies but come with higher maintenance and repair requirements.

Evolutionary history and ecological niche dictate which combinations have persisted, with convergent evolution (as in gill and lung surface area expansion) a testament to the universality of physical law and the versatility of life.

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in