Understanding cell membranes: structure, properties and transport

This work has been verified by our teacher: 23.01.2026 at 9:42

Homework type: Essay

Added: 17.01.2026 at 20:10

Summary:

Master cell membranes: structure, properties and transport, learn composition, membrane dynamics and key transport mechanisms with UK secondary examples.

Cell Membranes: Structure, Properties and Functions in Cellular Biology

The cell membrane, a fundamental structure surrounding all living cells and many of their internal organelles, functions as a selectively permeable barrier that regulates the passage of substances in and out of the cell, maintaining the essential differences between internal and external environments. More than a passive boundary, it is an active, dynamic and highly organised assembly, underpinning countless physiological processes. This essay will explore the molecular composition and organisation of cell membranes, elucidate their physical properties, analyse the primary mechanisms of transport across them, and examine how these features integrate into the broader context of cell function and health. Throughout, I will draw on examples and research relevant to the United Kingdom syllabi, progressing logically from structure to function to evaluation.---

Molecular Composition and Architecture of Cell Membranes

The architecture of cell membranes is underpinned by three major categories of molecules: lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, each fulfilling distinct and indispensable functions.Lipids: The Amphipathic Matrix

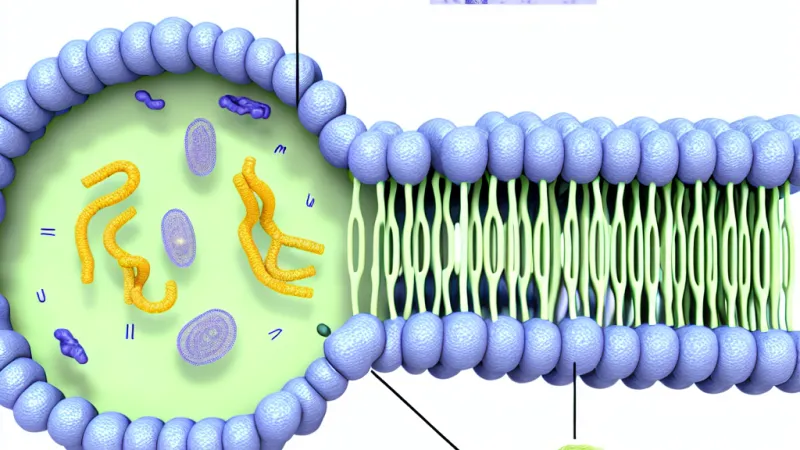

The structural backbone of cell membranes is a double layer (bilayer) of amphipathic lipids, predominantly phospholipids. This amphipathic nature—having both hydrophilic (water-attracting) heads and hydrophobic (water-repelling) tails—drives the spontaneous formation of bilayers in aqueous environments. The hydrophobic tails align inward, shielded from water, while the hydrophilic heads face the watery environments inside and outside the cell. Among phospholipids, phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine are prevalent, with sphingolipids and cholesterol contributing further complexity.Cholesterol, found in animal cell membranes, plays a critical role in modulating fluidity and packing of the bilayer, buffering against temperature-induced fluctuations—a contrast to plant membranes, which contain little or no cholesterol. In bacteria, hopanoids serve a similar function. Notably, the composition of the two leaflets of the bilayer is asymmetrical, with distinct distributions of certain phospholipids on the inner versus outer faces. Enzymes like flippases and scramblases help maintain or randomise this asymmetry, crucial for processes such as blood clotting and apoptosis in multicellular organisms.

Proteins: Function and Diversity

Embedded within or associated with the lipid bilayer are proteins, accounting for roughly half of the membrane's mass. Integral proteins, spanning the membrane with regions such as alpha-helices or, in some bacterial outer membranes, beta-barrels, serve as channels, transporters, pumps or receptors. For example, aquaporins facilitate water transport, while GLUT transporters enable glucose passage. Peripheral proteins, which attach loosely to the surface, often via interactions with lipid head-groups or integral proteins, participate in functions like anchoring the membrane to the cytoskeleton (e.g., ankyrin links the plasma membrane to spectrin in erythrocytes) or mediating cell signalling. The specific localisation of proteins is modulated by both their amino acid sequences and post-translational modifications, such as the addition of lipid groups (palmitoylation), which can target them to membrane sub-regions or microdomains.Carbohydrates: The Glycocalyx and Cell Identity

Carbohydrate chains, covalently attached to proteins (glycoproteins) or lipids (glycolipids), predominantly decorate the extracellular face of the cell membrane, forming the glycocalyx. This sugar-rich coating is vital for cell recognition, signalling, and adhesion. One familiar example is the ABO blood group antigens, which are determined by specific carbohydrate residues on red blood cell surfaces and form the basis for compatibility in blood transfusion—a point of practical importance in clinical medicine and readily tested in UK examination settings.---

Organisation and the Dynamic Nature of Membranes

A modern understanding of the membrane goes far beyond a static 'railway track' view. Instead, membranes are dynamic, fluid mosaics, with their constituents constantly shifting and rearranging.The Fluid Mosaic Model and Beyond

The fluid mosaic model, which emerged from the work of Singer and Nicolson in the early 1970s (as commonly referenced in A-Level biology textbooks), highlights the lateral mobility of proteins and lipids within the plane of the membrane. This fluidity is fundamental to membrane function. Factors influencing it include the degree of saturation of the fatty acid tails (unsaturated tails introduce kinks, preventing tight packing and increasing fluidity), chain length (shorter chains enhance fluidity), and cholesterol content (which both restricts movement at high temperatures and prevents stiffening at low ones).Homeoviscous adaptation is seen in poikilothermic organisms (e.g., cold-water fish), which alter the saturation of membrane lipids to maintain optimal fluidity as temperatures change—a concept commonly examined in A-Level specifications.

Microdomains and Organisation

The membrane is not homogenous. Cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich regions, termed lipid rafts, act as clustering points for certain proteins and play roles in signal transduction and trafficking. Caveolae, flask-shaped invaginations rich in the protein caveolin, also serve as important platforms for endocytosis and signalling. The role of membrane curvature, and the presence of specialised pits such as those coated by clathrin, further illustrate the organised complexity of the membrane surface.Experimental Evidence

Our knowledge of membrane dynamics is bolstered by techniques such as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), which demonstrates the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins, and freeze-fracture electron microscopy, which reveals the mosaic-like dispersion of proteins. Cell fusion studies—such as those fusing human and mouse cells—have shown mixing of membrane proteins over time, providing dramatic evidence of membrane fluidity.---

Selective Permeability and Movement Across Membranes

A key characteristic of the cell membrane is its selective permeability, meaning it allows certain substances passage while restricting others, based on factors such as size, charge, and solubility.Small non-polar molecules, like oxygen or carbon dioxide, as well as lipid-soluble substances, diffuse readily. In contrast, ions and large polar molecules require assistance. Quantitatively, according to Fick’s law, the rate of diffusion is proportional to the concentration gradient and surface area, and inversely proportional to membrane thickness. The partition coefficient, reflecting lipid solubility, is another useful predictor of permeability.

Membrane potential—an electrical gradient arising from selective ion diffusion—further affects charged solute movement. For example, the interior of animal cells is usually negative relative to the exterior, attracting cations and repelling anions. This sets up the electrochemical gradient, a fundamental driving force for many transport processes. The Nernst equation, occasionally discussed in advanced courses, allows calculation of the equilibrium potential for individual ions.

---

Mechanisms of Transport: Maintaining Homeostasis

Simple Diffusion

The simplest transport process, passive diffusion, requires neither energy nor membrane proteins. Gases like O₂ and CO₂ migrate along their concentration gradients, critical for processes such as gas exchange in the lungs’ alveoli and cellular respiration.Facilitated Diffusion

Large or charged molecules cross membranes via facilitated diffusion, using specific protein helpers. Channel proteins, like voltage-gated sodium or potassium channels in neurons, offer aqueous pores that permit rapid, selective passage of ions. These channels may open in response to stimuli such as voltage changes (as in nerve conduction), ligand binding, or mechanical deformation.Carrier proteins, such as the GLUT family for glucose, operate by a bind-and-flip mechanism: the solute binds, the protein changes conformation, and the cargo is delivered to the other side. Critically, facilitated diffusion always follows the concentration gradient and requires no external energy.

Osmosis and Water Potential

Osmosis is the net movement of water through a selectively permeable membrane from regions of higher to lower water potential. In plants, water potential incorporates both solute potential (Ψs) and pressure potential (Ψp); water moves to where overall Ψ is lower. Osmotic effects are central to plant cell turgor—loss of water (plasmolysis) causes wilting, whilst animal cells may burst (haemolysis) or shrivel (crenation) if exposed to imbalanced media. Aquaporin channels greatly increase membrane water permeability, facilitating rapid adjustment to osmotic stress.Active Transport

Active transport mechanisms move substances against their concentration gradients, necessitating energy, usually from ATP hydrolysis. The Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase, ubiquitous in animal cells, extrudes three sodium ions in exchange for two potassium ions per ATP molecule consumed, maintaining the steep ion gradients essential for nerve impulses and cellular homeostasis. Secondary active transport (co-transport) couples the favourable movement of one ion (often Na⁺) down its gradient to the uphill transport of another molecule. The sodium-glucose symporter in intestinal cells exemplifies this, using sodium’s inward drive to import glucose even when its concentration is higher inside the cell.Bulk Transport: Endocytosis and Exocytosis

Larger molecules or particles are moved via vesicular trafficking. Endocytosis encompasses pinocytosis (cellular ‘drinking’), phagocytosis (cellular ‘eating’), and receptor-mediated endocytosis (e.g., uptake of LDL cholesterol)—processes requiring the coordinated reshaping of the membrane and specialised protein coats like clathrin. Exocytosis, conversely, expels materials such as hormones or neurotransmitters, exemplified by synaptic vesicle release in neurons—a process orchestrated by SNARE proteins.---

Functional Integration and Illustrative Examples

The molecular machinery of membranes scales up to orchestrate essential biological functions.- Nerve Transmission: The sequential opening and closing of voltage-gated ion channels drive the nerve action potential, while the Na⁺/K⁺ pump restores ion gradients post-impulse. This process underpins every muscle contraction and thought. - Kidney Function: In the nephron, epithelial cells employ multiple membrane proteins to reabsorb salts and nutrients, critical for maintaining homeostasis and blood composition. - Plant Physiology: Proton pumps and ion channels in guard cells generate osmotic gradients, dictating stomatal opening for gas exchange—a process vital for photosynthesis.

Diseases like cystic fibrosis illustrate how membrane defects can have grave consequences; a mutation in the CFTR chloride channel disrupts water movement, causing thick, obstructive mucus in the lungs and other organs. Many drugs act by targeting membrane proteins—statins, for instance, block enzymes involved in cholesterol synthesis.

---

Critical Evaluation and Contemporary Perspectives

While the fluid mosaic model remains a cornerstone, it represents a simplification. Membranes display microheterogeneity, with transient raft domains and highly regulated organisation. Advances in lipidomics and proteomics reveal that membrane composition is more complex than previously thought. Experimental limitations mean that artificial membrane systems cannot fully recapitulate the diversity and dynamics seen in living cells, where the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix play crucial roles.Current research delves into topics like mechanobiology (how membranes sense and respond to mechanical forces), trafficking and membrane curvature, and biomedical applications, such as targeted drug delivery using liposomes and nanoparticles.

---

Rate:

Log in to rate the work.

Log in